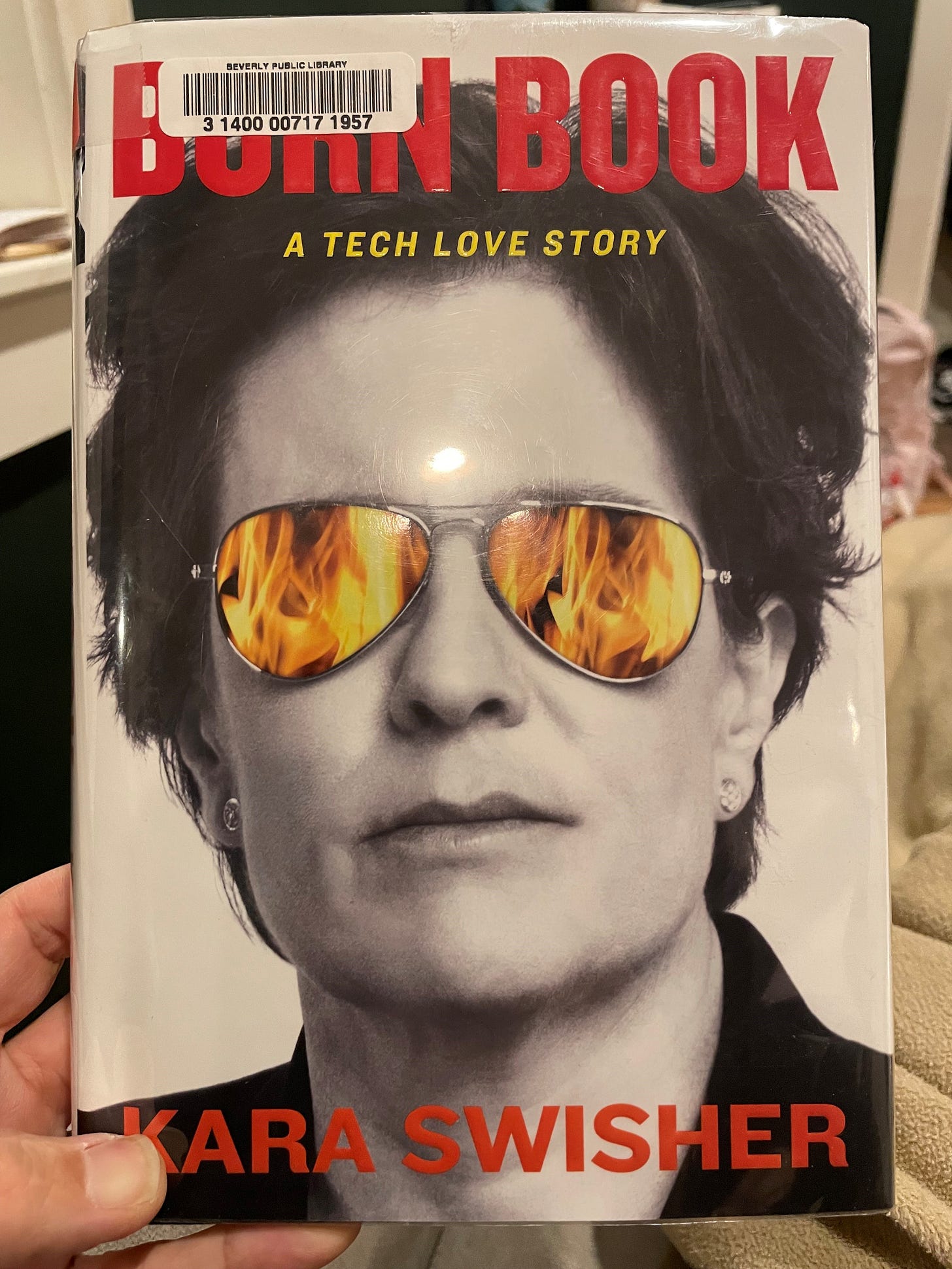

“I’ve never had any tolerance for move fast and break things,” says Kara Swisher, in Burn Book, her insightful and acerbic memoir of the rise of digital technology. “How about move fast and fix things?”

That struck me across the face.

I have been accused of taking a “move fast and break things” approach on more than one occasion. In my defense, I would point to a track record of innovation, increased revenues, and carefully controlled expenses. Hell, within the past two weeks I have referred to myself as a “preponderance of evidence professional,” who is confident that that I can provide much more value than cost for the disability community that I care about the most.

But progress comes at a cost. The bill always come due. Even in the transition from sheltered workshops and sub-minimum wage paying employment for people with disabilities in Massachusetts, some, far less than you would imagine, but some, disabled workers suffered. It was painful to see a minority of mostly older people with disabilities struggle as we transitioned from a segregated and tightly controlled workplace to a more independent and reasonably risky world. But the benefits of shuttering the workshops for the disability community were immense. Disabled workers who had previously earned as little as Twenty-Two Cents an Hour now enjoyed elevated levels of workforce engagement, increased earnings that were secured in a far shorter number of hours, and significantly increased connectivity to the shops, schools, YMCAs, and businesses and thriving life of their hometowns.

In my experience the primary opponents of integration were not workers with disabilities, but the nonprofit executives who had to alter their business models since the presence of disabled workers ensured consistent state billing and a reliable revenue stream. Seeing the funding for people with disabilities supporting the pursuit of their career goals in a more direct fashion was heartening.

When necessary, I don’t mind breaking things. I might as well be honest. Systems work according to design and I have participated in systems large and small that required breaking.

For instance, the mega churches that left 19-year-old me starry eyed about their ability to call people to Jesus and train him in his path too often ended up being little profitable fiefdoms that protected the power of their leaders and later served as a core of support for America’s most vulgar and autocratic leader. I still remember the boomer pastors that preceded my generation claiming that there was a “leadership gap,” among my peers, because we would not sacrifice our lives and callings to sustain their professional legacy.[1] Cue the Generation X’s emergent conversation, the millennial attraction to deconstruction, #ChurchToo and the daily exposure of church trauma being reported on in The Roys Report.

Likewise, I spent over a decade of my life in a disability nonprofit that had to be constantly convinced in economic terms (margin over expenses, 15% at the end of every year please) that focusing on the outcomes of the people it served was more important than providing upper middle-class incomes for its executives[2] and low wage with the promise of stability employment for line employees. For a bright season at that nonprofit we produced so many innovative resources for the disability community that the organization was on the verge of becoming the maker space for access and inclusion that we I had long hoped it would be. Unfortunately, the self-interest and insecure cling to hierarchy practiced by its executives and the staff’s preference for stability over growth trajectory snuffed the spark of innovation. Admittedly, this was in my own move fast to break and build things area. I made plenty of mistakes, many of which have been documented in this space and even more that I am willing to share with you should you ask. I’ve mostly healed from the failure of the innovation space and I think my former organization is on the rebound. Still, it was difficult to watch an organization I poured myself out for slide into the bleak country of human service standard.

All that said, I do not think that what Swisher is asking us to neglect necessary breaking. I think she is challenging us to only break in the service of building. If I challenge myself to direct my energies towards that end, I can focus on:

Training my vision on what an integrated workforce looks like and working backwards from that goal to develop the systems that are required to equip people with diverse abilities to establish and grow their careers. I have recently experienced the power of letting the ends clarify the means. A little over a year ago I freaked out upon first visiting JVS Boston and Quincy College’s multi-million-dollar ArLab biotechnology and healthcare training center. Instead of surrendering to my anxiety about how many people with diverse disabilities would benefit from the space, I immediately started to think about how we could get young adults with disabilities to start their careers earlier. I am confident that an early career launch will provide a stronger foundation upon which career seekers with disabilities can stack the higher-level skills required to grow into careers as Central Sterile Processing Techs, Certified Nursing Assistants, or Biotechnology Lab Technicians. My JVS team is now in the second year of a pilot initiative called Work Early, Expect Success that provides industry education and connections to subsidized youth employment for 14 - 16 year old students with disabilities with industry education and connections to part time employment while also supporting their parents in developing high expectations of employment and skills to navigate common barriers (i.e., working while receiving benefits and transportation challenges) so that they can support their student’s success. I cannot wait to meet the first ArLab graduate who first caught a passion for their Allied Health or Biotechnology career when they were a freshman in high school.

Recognizing that loneliness and social isolation are significant threats to the wellbeing of the disability community[3] so that I can more effectively equip clients to foster strong social connections as they grow their careers. I know that grabbing the occasional drink after work or joining colleagues for a game out at Fenway is important, but I have often under-emphasized the social needs of my clients and expected them to get social supports from another provider’s Community Based Day Program, nonprofits like Special Olympics, or local community groups like the YMCA. Removing social connection from my area of interest reduces the access clients have to my rather substantial network of resources. Failing to work with my clients to cultivate healthy relationships can also underestimate the power that work friendships can have in sustaining and catalyzing their careers.

Developing the beloved community through a practice of calling in rather than the more antagonistic practice of calling out. Haranguing people in power comes naturally to me. I am sorely tempted to unleash this power on a daily basis during this season when so many of my countrymen appear more fascinated with self-serving populism than they are in trusting data about existential challenges and trusting people with expertise to develop solutions. However, I suspect that my cutting comments and snarky assertions are an ineffective means of persuasion. Moreover, I try to follow this guy who embodied grace and charged us to “do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, (and) pray for those who abuse you.”

I cannot claim to have ever mastered the latter practices or even to have followed them often. In fact, after I initially drafted this paragraph I spent the whole walk from the train station to work bitching to my friend Peter about my perceived political enemies. But I strongly suspect that laying just underneath the anti-immigrant and let’s go petroleum sentiments of my countrymen is a deep substratum of fear. The world has changed significantly in my lifetime. Almost every country is now connected via fiber optics and finances, our neighbors are as likely to be from Seattle, Seoul, or Port-au-Prince as they are to be local high school graduates, and we live in less fear of nuclear than environmental catastrophe. I want to empathize more with this sense of terror in hope that together we might find a way forward. This desire is the sole reason that I chose not to share and denounce images of an American politician giving a Sieg Heil. Baby steps.

The world is unraveling and we make our way by mending. I don’t know who initially shared this wisdom with me. I would not be surprised if it was my beloved Rev. Everett, leader of the Massachusetts Council of Churches and pastor of The Mending Church. My prayer, as I prepare to disembark this train and walk to my office where I will be greeted by the call to live the Jewish practice of Tikkun Olam[4] on the wall, is that I will chose to mend more than rend in the years to come.

When needed, please remind me of this intention.

[1] Which, often, were churches that looked and felt like Target and peddled discipleship at a discount.

[2] Of which I was one.

[3] Much like everyone else. Yay inclusion.

[4] Repairing the world.

I've missed reading your pieces, Jeff. Nice one today!